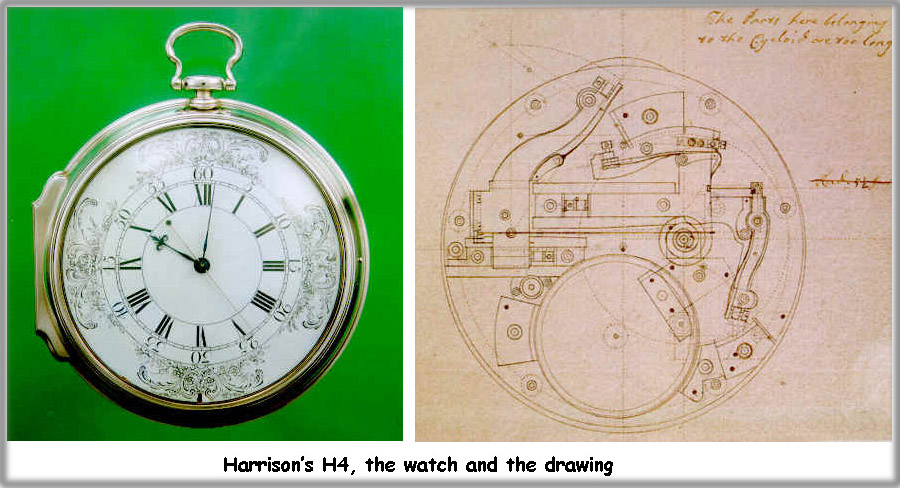

The five watches pictured above may look like enormous pocketwatches, but in fact they are the last and amongst the finest in the line of chronometers (in the original sense, that is: a clock of high precision, accuracy and isochronism) stretching forward from John Harrison's H4 of 1764, the seagoing clock which won the enormous cash prize offered by the British Board of Longitude for inventing this vital navigational instrument:

Although pocketwatches were known in Harrison's time, they were large, and rare and expensive, and not remotely capable of keeping time well enough for navigation. Harrison's earlier efforts were variations on much larger portable clockworks, but the 3-pound, 5-inch-diameter H4 was truly revolutionary, capable of timekeeping comparable with the finest stationary clocks even while tumbling atop the ocean waves.

Thus was born the progenitor of over 200 years of marine chronometers, those lovely watches with their tall, cylindrical movements, mounted on leveling gymbals and cased in double boxes:

Obviously, these beauties are a lot more like portable clocks than what we are used to considering watches, the whole construction being even larger and heavier than Harrison's! Still, boxed chronometers functioned so well that they continued to serve many oceangoing vessels right on through the era of quartz-controlled clocks; it took the widespread use of GPS to finally send them into complete retirement.

Click the pictures for even larger!

Deck watches, like those above, dated from the early 1900's or later, and incorporated the century-and-a-half of watchmaking progress since Harrison. Developments in precision manufacturing, interchangeable parts, lubrication, and escapement and balance design allowed considerable cost savings and miniaturization, while timekeeping approached the standards of the boxed chronometers. Generally a deck watch was used as a secondary timepiece, to be wound and synchronized daily with the ship's official clock. As a result, its prime requirement was isochronism, the consistency of timekeeping hour-to-hour, day-to-day, over months and years. It was of less concern that it might be a few seconds fast or slow each day, than that the rate remain constant. Thusly could be supplied a portable copy of the master clock (which required a dial-up position, and probably resided in the instrument room), a watch which required minimal daily attention to usefully provide the time at a remote location, and also serve as backup in case of a problem with the ship's main clock.

The four watches presented here were all produced in the 1940s and 1950s, but are otherwise a diverse group. Ranging in diameter from 60-70mm, they are variously French (Auricoste), British (E.M. Tissot), German (Stowa) and American (Hamilton). Designed for critical use rather than style, all feature basic black markings on white or neutral dials, large, full Arabic numerals (except the Tissot's inexplicable Romans) and distinct minutes tracks, and perfectly-sized, blued or blackened Poire hour and simple minute hands. The dials are large, high-contrast and plain, perfect for precise setting and instant reading.

I find there is a lot to like about deck watches, their design is purposeful and harmonious, their size and packaging are appropriate to a personal desk clock, and I love the loud, slow tick. Like other military watches, each carries both individual and collective history, touched by people and places, and events of import. Finally, the stringent timekeeping requirements, unique format and intended usage have all conspired so that these watches house rare and exceptional movements. Hand-bent overcoil hairsprings, huge screwed balances and beautiful and sophisticated regulators are the norm, and whether the bridges are striped, lapped or gilt, they are uniformly well-finished. Remember, the prime requirement is consistency over time and circumstances, and these watches are designed to run well for long periods without special care.

In addition to the pictures and comments below, each of these watches is profiled with more and larger pictures at these links:

......

......  ......

......

......

......

......

......

I hope you enjoyed this!

SteveG

June 7, 2006